Q&A

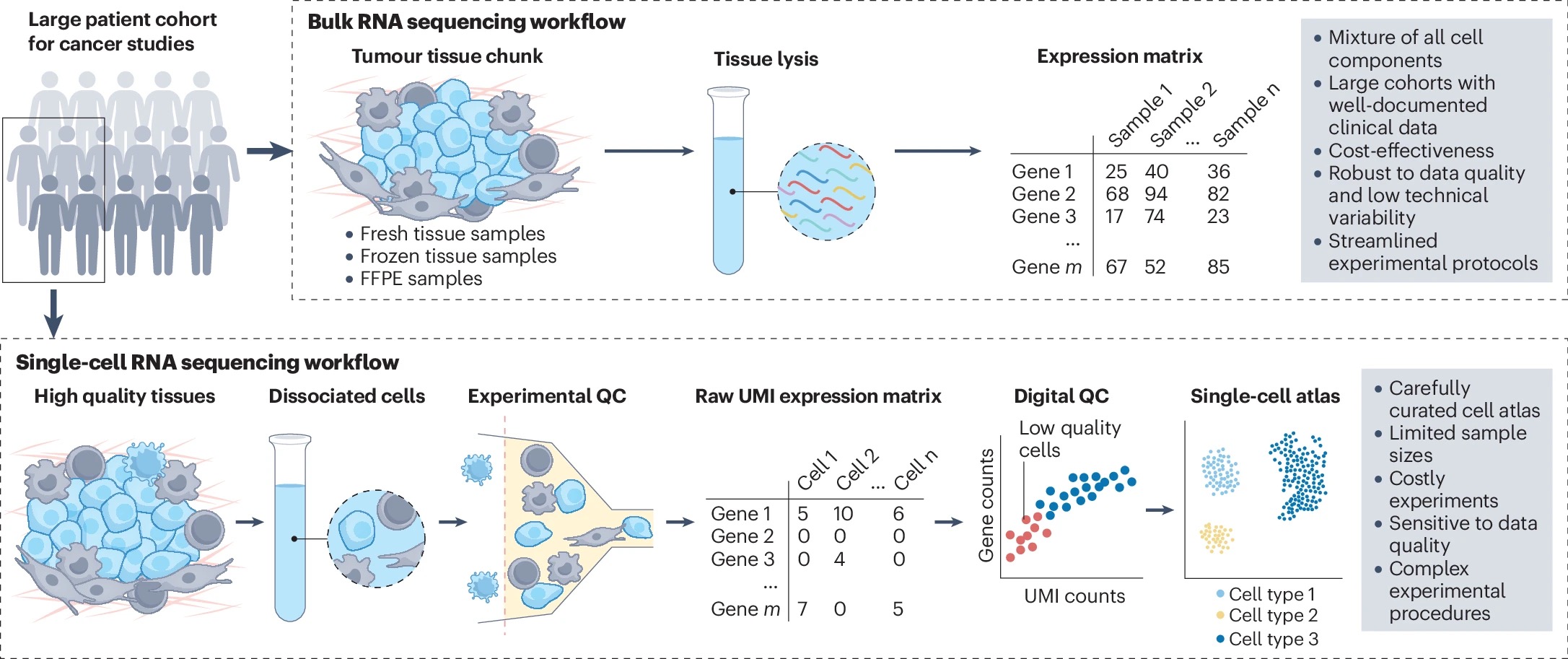

This review synthesizes three interconnected themes that reshape cancer transcriptomics. First, we address the critical need to bridge single-cell and bulk RNA-seq data, recognizing that while single-cell approaches excel at resolving cellular heterogeneity, bulk RNA-seq remains indispensable for large-scale clinical studies with long-term outcome data. Second, we systematically document why cancer presents unique computational challenges compared to normal tissues, particularly tumor cell plasticity and the profound heterogeneity that violates core assumptions of methods developed for healthy tissues. Third, we demonstrate how deconvolution translates from methodology to clinical impact through applications in tumor subtyping, treatment response prediction, and biomarker discovery.

The major unresolved questions center on what we call the "missing reference" problem: how to create comprehensive profiles that capture dynamic tumor cell states rather than assuming stable expression patterns. We also identify critical benchmarking gaps, as most validation studies use peripheral blood or cell lines rather than actual tumor tissues, and the ideal approach of generating matched bulk and single-cell data from identical samples remains technically challenging and rarely performed.

Looking forward, emerging directions include adapting deconvolution for FFPE samples to unlock vast clinical archives, developing temporal models that capture how cellular compositions evolve during treatment, integrating multi-modal data including copy number and methylation patterns, and extending these approaches to spatial transcriptomics to understand not just what cell types are present but where they reside and how they interact within the tumor architecture.

Reviewers particularly valued our comprehensive cataloging of 43 deconvolution methods with clear applicability classifications and the decision-tree framework in Figure 4, which transforms what could have been a technical comparison into actionable guidance for method selection. They emphasized our cancer-specific focus, noting that while many existing reviews use peripheral blood or cell-line mixtures for validation, we systematically address the unique challenges of tumor tissues including cellular plasticity and microenvironment complexity. Our balanced and transparent approach was repeatedly commended, especially our honest assessment of method limitations and clear documentation of which methods have rigorous cancer-specific validation versus those claiming applicability without proper benchmarking. The collaborative expertise spanning our fifteen-year method development history with DeMix, DeMixT, and DeMixSC to broader cancer genomics perspectives was recognized as strengthening both technical depth and practical relevance, creating a resource that bridges computational biologists with experimental researchers and clinicians.

In the near term, this review enables researchers to re-analyze thousands of existing bulk RNA-seq datasets from TCGA and other sources to extract tumor microenvironment composition and tumor-specific signals, potentially discovering new biomarkers without generating new data. Our framework provides a roadmap for clinical trials already incorporating deconvolution as secondary outcomes and identifies specific gaps in FFPE optimization, temporal modeling, and rare cell detection that method developers need to address.

Looking three to five years ahead, the clinical impact could be substantial as deconvolution-derived metrics like tumor-specific mRNA abundance and immune cell proportions become validated prognostic markers. As immunotherapy expands, tumor microenvironment profiling through deconvolution could predict treatment response, while extracting tumor-specific expression profiles may enable more accurate molecular subtyping. We hope this review establishes validation standards, serves as an educational resource, and facilitates collaboration between experimentalists and computational researchers by providing a common framework for understanding what these methods can accomplish in cancer research.

The review emerged from a practical challenge we observed through years of collaborating with experimental biologists: despite our lab's fifteen-year history developing deconvolution methods, cancer researchers consistently struggled with knowing which method to choose, and many tools developed for normal tissues failed when applied to tumors. This motivated us to create a cancer-specific guide rather than a general methods review. The literature curation was our most intensive phase, systematically identifying 43 relevant methods while establishing clear criteria for what to exclude, ultimately documenting all decisions transparently in supplementary materials.

Developing the conceptual framework requires multiple iterations, constantly asking ourselves whether a cancer researcher without computational training could understand and apply our guidance. We organized the work by expertise areas, with different team members leading sections on single-cell methods, semi-reference approaches, reference-free methods, and clinical applications, while ensuring integration across the entire manuscript. The figures, especially the decision tree guiding method selection, went through numerous revisions to achieve clarity. After submission, reviewer feedback helped us strengthen the cancer-specific emphasis and expand clinical examples, while the final editing involved careful attention to scientific nomenclature and journal style requirements.

The most significant turning point came when we realized we couldn't simply rank methods as "best" because performance depends so heavily on individual contexts—available reference data, target cell types, research questions. We initially drafted ranking tables but kept finding exceptions that made them meaningless. Accepting this complexity and shifting to decision trees was frustrating at first, since everyone wants simple recommendations, but it made the review genuinely useful.

Coordinating across time zones meant real logistical challenges, and we had substantive disagreements about classifying certain methods that required iterative discussion rather than quick resolution. The debate about documenting excluded methods in Supplementary Table 2 was practical because we'd identified many methods that didn't fit our criteria, and while documenting exclusions took extra work, we chose transparency. What genuinely surprised me was discovering how few clinical trials use deconvolution beyond exploratory analyses despite years of methods development. This gap between computational capabilities and clinical application became a theme shaping our emphasis on translational barriers.

We're immediately developing practical tutorials on constructing cancer-specific references, interpreting deconvolution results, and avoiding common pitfalls to make these methods more accessible. We're collaborating with scientists generating matched bulk and single-cell datasets to address the benchmarking gaps we identified. Additionally, we're actively developing approaches following suggestions in the future work section of the review. For example, there are missing opportunities in spatial transcriptomic deconvolution, for which we developed DeMixNB; the manuscript is available as a preprint.

Biostatistics brings essential rigor to AI development that machine learning alone cannot provide. While AI methods show impressive performance metrics, biostatisticians ensure those metrics reflect real-world performance rather than artifacts of simulated data, assess whether models generalize across cancer types, and provide the uncertainty quantification critical for clinical decisions, since most AI approaches give only point estimates without confidence intervals. We also address data quality issues like batch effects that AI might inadvertently learn, curate training datasets that avoid systematic biases, and detect when reference profiles don't match target tissues.

What makes this review distinctive is its problem-oriented organization around biological questions cancer researchers actually face rather than computational methods themselves, making it actionable for experimentalists starting with cancer biology problems. We deliberately discussed limitations openly, including when deconvolution struggles with rare populations, highly plastic tumor cells, or FFPE samples, because this honesty helps researchers avoid misapplication and builds realistic expectations.

The key insight from developing this review is that our field's biggest barrier isn't computational sophistication but effective translation. We have powerful methods, yet researchers struggle with selection, validation standards remain inconsistent, and pathways to clinical application are unclear. Short-term, we anticipate better cancer-specific benchmarks and FFPE-optimized methods emerging. Longer-term, deconvolution could become routine clinical practice, enabling real-time treatment monitoring. Progress requires not just better algorithms but improved communication between computational and experimental researchers. This review represents our contribution toward building those bridges, helping more researchers extract meaningful insights from bulk transcriptomic data to advance cancer biology and improve patient outcomes.